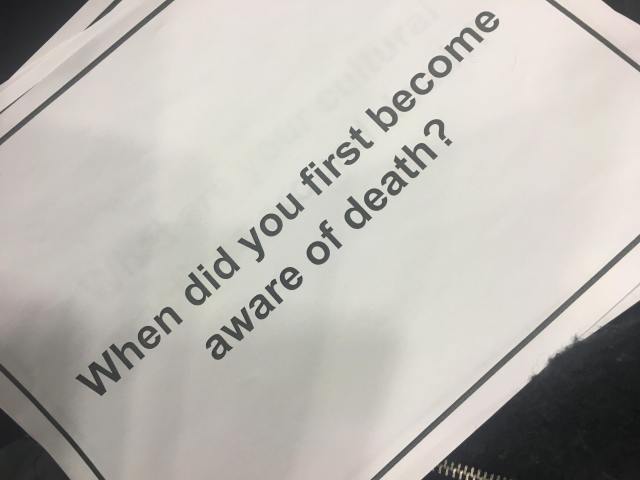

As part of the ARTivism Lab Speaker Series, hosts Eliza Chandler and Esther Ignagni facilitated a Death Cafe on Ryerson’s campus. Aimed at bringing space to conversations typically silenced within Western cultures, Death Cafes work to create casual conversations around the typically muted subject. While often sensationalized in mainstream media, the concept of death often goes unmentioned or talked about within social settings. Revolving largely around the centrality of death within disabled identities, the event brought attention to the lack of space provided for people with disabilities within the public sphere. After a brief overview of central concepts and guidelines, guests of the ARTivism Lab Speaker Series were encouraged to form smaller groups to continue conversing. Acknowledging the possible discomfort accompanying such conversations, questions which acted as prompts were provided to further facilitate discussion.

Upon breaking up into groups to discuss death further, we initially began by talking about how frequently we all individually think about dying. While being able to approach death in a relatively casual and positive light, I would not say it is at the forefront of my mind on a daily basis. This is different than that of a person living with a disability, for death is central to the discourse of disability. As stated by Chandler and Ignagni, “death is more imaginable than a life with difference” (2). Such notion is aided by a lack of accommodation in physical spaces, which work to restrict and silence disabled voiced through a lack of access. This lack of access further perpetuates the belief of death being a more desirable option for those living with a disability. In addition to physical spaces, individuals with disabilities also experience a death of culture when their cultural needs (ASL) go unmet. Discussing the portrayal of disability within cinema, Hayes states that in movies “the ultimate paternalistic act in these movies is the death or murder of the disabled character”. The silencing of people with disabilities through confinement or death is often seen from an able-bodied viewpoint as an easier and more attractive option than the accommodation of differences. My lack of consideration about death is indicative of my able body, as dying is not central to my identity.

As a whole, I enjoyed attending my first Death Cafe. Discussing the prospects of dying in such a social atmosphere brought attention to the importance of such conversations. I believe that the role of death is to make our finite lives more meaningful. While I appreciated having the time to discuss the topic of death in such a casual manner, I acknowledge the privilege present in being able to do so. I personally approach death in a relatively positive light and am therefore comfortable conversing about it, however I am also lucky enough to be in a position where death has not significantly impacted my life. For example, I live with no life-threatening ailments nor has anyone extremely close to me ever passed away (despite grandparents, who fortunately died peacefully prior to my birth, or well into their eighties/nineties). In such cases, I imagine the topic would carry a heavier weight. However it is in these scenarios where the practice of the Death Cafe may be of even greater use.

Works Cited

Chandler, Eliza, and Esther Ignagni. “Strange beauty: Aesthetic possibilities for desiring disability into the future.” Ryerson University. Accessed 6 March 2018.

Hayes, Michael. “Troubling Signs: Disability, Hollywood Movies and the Construction of a Discourse of Pity.” Disability Studies Quarterly, vol. 23, no. 2, 2003, http://dsq-sds.org/article/view/419/585